C++ is a general-purpose, multi-paradigm programming language designed/developed by Bjarne Stroustrup which alongwith C, forms the backbone of majority of the programming industry today. A very important concept to be grasped by beginner programmers is the idea of “linking”. Linking basically refers to the process of bundling library code into an archive and use it later when necessary. It turns out to be an idea that is used extensively in production. The following article aims at presenting a broad view of “linking”.

The three fundamental features which make C++ special are:

- Zero cost abstractions

- Generic programming

- Fairly low level

Being developed on the principle of you don’t pay for what you don’t use, C++ allows us to write high-performant, efficient code. Comparison of Deep Learning software clearly shows that most of the deep learning libraries use C++ as one of their core programming languages.

For those who want to follow along, I’ll be using a Linux environment throughout with a GCC compiler.

[rohan@rohan-pc ~]$ g++ --version

g++ (GCC) 7.4.1 20181207

Copyright (C) 2017 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

This is free software; see the source for copying conditions. There is NO

warranty; not even for MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE.

[rohan@rohan-pc ~]Before we begin let’s answer the most important and relevant question question in this regard.

Why do we need linking in C++ ?

You might be wondering that what’s wrong in putting all my source codes in source files (with .cpp, .cc, .cxx, .c++ etc extensions) and then compile all of them to build the final executable. Well, there’s nothing wrong, but as the size and complexity of the program grows, you might end up having hundreds of source files. At this scale, the compilation of the project takes a lot of time and doing this every single time severely hampers the traditional compile-run-test-debug cycle which is impractical.

Moreover storing large projects purely in the form of source files take up a lot of space. If you are writing a closed source library which you want to distribute, for example, the Intel Math Kernel Library, which is a very fast, closed source, Linear Algebra library; you would want ship your library API to other programmers so that they can use it in their code, without releasing your implementation; source files are simply out of the question in this scenario.

The solution to the above problems is using some sort of binary files which are present in an encoded form (zeroes and ones) and are compressed, so that they take up less space than raw source files. To be more precise, this is applicable only when we are using dynamic linking because as we will see static libraries consume a lot more space. These files can then be somehow linked to your source files and not recompiled every time you make changes to your own application source files thus vastly speeding up the compilation process. In general, whenever we are trying to use a block of code containing some functions or class definitions etc, which are not defined in our current source file or not present in the header files we included, the linker comes into play.

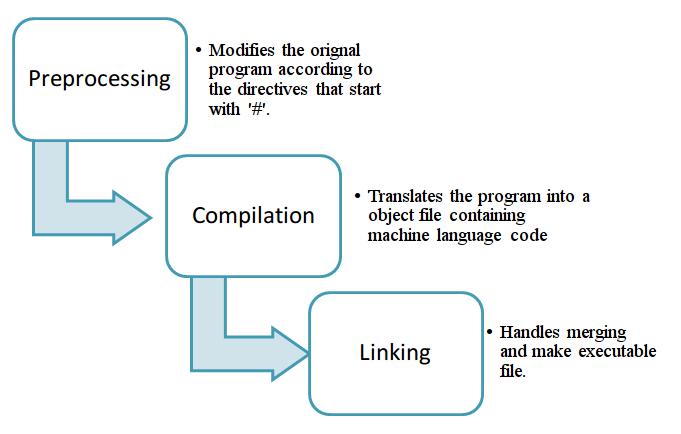

Overview of the C++ compilation steps:

This technique of linking is so important and widely used, that in case you didn’t know about it, you were using it all this time unknowingly! Let’s investigate a simple hello world code in C++ as a motivational example:

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

std::cout << "Hello World\n";

}And running the commands:

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ g++ test.cpp

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ ./a.out

Hello World

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ ldd a.out

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffcb0f66000)

libstdc++.so.6 => /usr/lib/libstdc++.so.6 (0x00007f7c3ce0e000)

libm.so.6 => /usr/lib/libm.so.6 (0x00007f7c3cc89000)

libgcc_s.so.1 => /usr/lib/libgcc_s.so.1 (0x00007f7c3cc6f000)

libc.so.6 => /usr/lib/libc.so.6 (0x00007f7c3caab000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 => /usr/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007f7c3d00c000)Here, libstdc++ is GNU’s implementation of the C++ Standard Library which is automatically linked dynamically to your executable binary i.e. a.out. The ldd command lists the runtime library dependencies. libc is the C Standard library which is also linked dynamically. Let us now try to link the standard libraries statically so that our new executable a1.out does not have any runtime dependencies. This can be conveniently done in GCC with the help of the -static flag.

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ g++ test.cpp -o a1.out -static

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ ./a1.out

Hello WorldSo far so good. Let us now run the ldd command on a1.out and investigate the sizes of the executable binaries:

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ ldd a1.out

not a dynamic executable

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ ls -l

total 2124

-rwxr-xr-x 1 rohan rohan 2150128 Jan 27 04:05 a1.out

-rwxr-xr-x 1 rohan rohan 17056 Jan 27 04:01 a.out

-rw-r--r-- 1 rohan rohan 68 Jan 27 04:01 test.cppThe output of the ldd command on a1.out is quite expected but on comparing the sizes of a.out and a1.out, the results absolutely astonishing ! The size of a.out is 17,056 bytes whereas that of a1.out is 2,150,128 bytes which is about 126 times more than the size of a.out. That, hopefully, gives you an idea of the size difference between shared and static libraries. In the above example, even though we ourselves have written very little code, the C and C++ standard libraries which we had statically linked contains a lot of code which resulted in a very fat binary.

We will now delve into the details of static and dynamic linking.

Static Linking

In static linking, the linker makes a copy of the library implementation and bundles it into a binary file. This binary is then linked to the application codes to produce the final binary. Let us understand this concept clearly with a hands-on example.

In this example, we will be creating our own extremely simple Integer class which has a constructor, an add(..) and a display(..) function. Create a header file example.hpp having the following code:

#include <iostream>

struct Integer

{

int data;

Integer(const int &x);

Integer add(const Integer &x);

void display();

};Create a source file named example.cpp to implement the functions:

#include "example.hpp"

Integer::Integer(const int &x)

{

data = x;

}

Integer Integer::add(const Integer &x)

{

return Integer(data + x.data);

}

void Integer::display()

{

std::cout << "Integer value : " << data << '\n';

}Finally create an application file test1.cpp to consume our Integer class:

#include "example.hpp"

int main()

{

Integer a(12), b(45);

Integer c = a.add(b);

c.display();

}Our directory tree should now look like:

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ tree

.

├── example.cpp

├── example.hpp

└── test1.cpp

0 directories, 3 filesA static library, by construction, is a library of object codes which when linked at compile-time, becomes a part of the application with no dependencies at runtime. So let’s create that object code now.

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ g++ -fPIC -c example.cppThis creates a new object file example.o. The -c flag tells GCC to stop after the compilation process and not run the linker and the -fPIC flag stands for position independent code which is required for shared libraries but we will also use them for static linking to maintain uniformity.

Now we will be creating the static library using the ar command.

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ ar -cq libexample.a example.oHooray ! Our static library libexample.a is now ready. ar is GNU’s Archive tool. For more details check out the flags and the manual. Our directory structure should now look like:

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ ls -l

total 20

-rwxrwxrwx 1 rohan rohan 136 Jan 6 21:45 example.hpp

-rw-r--r-- 1 rohan rohan 3240 Jan 26 18:16 example.o

-rwxrwxrwx 1 rohan rohan 233 Jan 6 21:44 ex.cpp

-rw-r--r-- 1 rohan rohan 3468 Jan 26 18:23 libexample.a

-rwxrwxrwx 1 rohan rohan 107 Jan 26 18:01 test1.cppTo get a more insights into our static library, let’s generate the symbol table for libexample.a:

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ nm -gC libexample.a

example.o:

U __cxa_atexit

U __dso_handle

U _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_

U __stack_chk_fail

000000000000001c T Integer::add(Integer const&)

0000000000000078 T Integer::display()

0000000000000000 T Integer::Integer(int const&)

0000000000000000 T Integer::Integer(int const&)

U std::ostream::operator<<(int)

U std::ios_base::Init::Init()

U std::ios_base::Init::~Init()

U std::cout

U std::basic_ostream<char, std::char_traits<char> >& std::operator<< <std::char_traits<char> >(std::basic_ostream<char, std::char_traits<char> >&, char)

U std::basic_ostream<char, std::char_traits<char> >& std::operator<< <std::char_traits<char> >(std::basic_ostream<char, std::char_traits<char> >&, char const*)Let’s now create our final executable test1 using our static library. It is to be noted that during compilation the linker should find our static library to successfully link it to our executable binary. So we should compile our test code test1.cpp as:

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ g++ test1.cpp -L. -lexample -o test1Please look at the above command very carefully. The -L flag gives the path of the directory in which the linker should search for libraries to link. It can be written as -L followed by the path. In our case it is the current directory so you can use -L.. The -l flag gives the name of the library to be linked. The shared/static libraries always start with lib and so it is avoided and we can simply write -lexample to link with libexample.a.

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ ./test1

Integer value : 57

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ ls -l

total 40

-rwxrwxrwx 1 rohan rohan 136 Jan 6 21:45 example.hpp

-rw-r--r-- 1 rohan rohan 3240 Jan 26 18:16 example.o

-rwxrwxrwx 1 rohan rohan 233 Jan 6 21:44 ex.cpp

-rw-r--r-- 1 rohan rohan 3468 Jan 27 02:53 libexample.a

-rwxr-xr-x 1 rohan rohan 17592 Jan 27 02:53 test1

-rwxrwxrwx 1 rohan rohan 107 Jan 26 18:01 test1.cppNow it compiles and runs fine. When example.a is in a different directory, the entire path to it needs to be provided. Let’s run the ldd command on test1.

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ ldd test1

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffeb4ffa000)

libstdc++.so.6 => /usr/lib/libstdc++.so.6 (0x00007fbaa4fbf000)

libm.so.6 => /usr/lib/libm.so.6 (0x00007fbaa4e3a000)

libgcc_s.so.1 => /usr/lib/libgcc_s.so.1 (0x00007fbaa4e20000)

libc.so.6 => /usr/lib/libc.so.6 (0x00007fbaa4c5c000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 => /usr/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007fbaa51b8000)We can only see .so files i.e. shared libraries. These are runtime dependencies of test1. We cannot find any static libraries listed as a dependency. Thus you can try deleting example.a or libexample.a and then running test1. It’ll run fine as usual as it already has been bundled into our executable binary test1. Another important thing to remember is that no matter how many times we want to make changes to test1.cpp we need not recompile example.cpp ever again.

Dynamic Linking

In dynamic linking, the library object code is linked to the executable binary at runtime. So, now we have a runtime dependency on the library file. If that shared object (.so file) is not discoverable at runtime, the executable binary won’t run. Let’s understand dynamic linking with the help of the same example we used to understand static linking.

The shared library libexample.so is created using the following command:

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ g++ -shared -o libexample.so example.oThe -shared flag tells GCC that a shared library is requested to be created. The symbol table of the newly created shared library can be generated in the same manner as we did before:

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ nm -gC libexample.so

U __cxa_atexit@@GLIBC_2.2.5

w __cxa_finalize@@GLIBC_2.2.5

w __gmon_start__

w _ITM_deregisterTMCloneTable

w _ITM_registerTMCloneTable

U __stack_chk_fail@@GLIBC_2.4

0000000000001196 T Integer::add(Integer const&)

00000000000011f2 T Integer::display()

000000000000117a T Integer::Integer(int const&)

000000000000117a T Integer::Integer(int const&)

U std::ostream::operator<<(int)@@GLIBCXX_3.4

U std::ios_base::Init::Init()@@GLIBCXX_3.4

U std::ios_base::Init::~Init()@@GLIBCXX_3.4

U std::cout@@GLIBCXX_3.4

U std::basic_ostream<char, std::char_traits<char> >& std::operator<< <std::char_traits<char> >(std::basic_ostream<char, std::char_traits<char> >&, char)@@GLIBCXX_3.4

U std::basic_ostream<char, std::char_traits<char> >& std::operator<< <std::char_traits<char> >(std::basic_ostream<char, std::char_traits<char> >&, char const*)@@GLIBCXX_3.4Let us now create the final executable binary and run it:

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ g++ test1.cpp -L. -lexample -o test1

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ ./test1

Integer value : 57Now it all looks very familiar and is exactly the same as static linking. But let’s have a look at the directory structure and the sizes of the files:

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ ls -l

total 56

-rwxrwxrwx 1 rohan rohan 136 Jan 6 21:45 example.hpp

-rw-r--r-- 1 rohan rohan 3240 Jan 26 18:16 example.o

-rwxrwxrwx 1 rohan rohan 233 Jan 6 21:44 ex.cpp

-rwxr-xr-x 1 rohan rohan 16744 Jan 27 02:42 libexample.so

-rwxr-xr-x 1 rohan rohan 17128 Jan 27 02:46 test1

-rwxrwxrwx 1 rohan rohan 107 Jan 26 18:01 test1.cppIf you compare the size of test1 executable now and in the case of static linking, you’ll notice that in the previous case, it was 17592 Bytes and now it is 17128 Bytes. The 464 bytes of memory savings is due to linking it dynamically at runtime rather than bundling it into test1. You might say that 464 bytes is an absolutely negligible amount of memory, but then the shared and static libraries we have created hardly have any code in them, the Integer class having only a constructor and two methods all of which being one liners. As the source code size increases, it begins to create massive differences like the Hello World program I demonstrated in the beginning. Let’s us do something interesting. We will move libexample.so to a different directory and then try running test1 see what happens!!!

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ mv libexample.so ~/libexample.so

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ tree

.

├── example.hpp

├── example.o

├── ex.cpp

├── test1

└── test1.cpp

0 directories, 5 files

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ ./test1

./test1: error while loading shared libraries: libexample.so: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directoryYou might have expected this because the runtime linker cannot find libexample.so. This can be fixed by altering the LD_LIBRARY_PATH environment variable available in Linux. Since the linker searches for the shared object at runtime, recompilation is no longer needed. We just have to append the path which the linker can search at runtime to the LD_LIBRARY_PATH variable and then run test1.

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ export LD_LIBRARY_PATH=~:$LD_LIBRARY_PATH

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ ./test1

Integer value : 57Thus we can edit the path to be searched by the linker at runtime! Thus both static libraries and shared libraries have their own pros and cons. Static libraries will be used when speed is important and the size of the executable binary is not important and no runtime dependencies should be involved. On running the ldd command on test1, libexample.so is clearly listed as a runtime dependency found at /home/rohan (my ${HOME} directory):

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ ldd test1

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007fff1c1f3000)

libexample.so => /home/rohan/libexample.so (0x00007f776e456000)

libstdc++.so.6 => /usr/lib/libstdc++.so.6 (0x00007f776e264000)

libm.so.6 => /usr/lib/libm.so.6 (0x00007f776e0df000)

libgcc_s.so.1 => /usr/lib/libgcc_s.so.1 (0x00007f776e0c5000)

libc.so.6 => /usr/lib/libc.so.6 (0x00007f776df01000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 => /usr/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007f776e462000)Shared libraries are used to reduce the size of the executable binary and to share code at runtime. Moreover, it’s extremely useful in making changes to the underlying library at runtime without affecting the client code. Let’s see how it is done.

Let us edit the ex.cpp file and add an extra line to the display function:

void Integer::display()

{

std::cout << "This is the new display function\n";

std::cout << "Integer value : " << data << '\n';

}We will now compile it, create the shared library and use it in our production code:

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ g++ -fPIC -c ex.cpp -o example.o

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ g++ -shared -o libexample.so example.o

[rohan@archlinux LinkingExamples]$ ./test1

This is the new display function

Integer value : 57That’s it ! We don’t have to recompile test1.cpp. Just simply recompile our shared library. This is a very useful feature of shared libraries. With shared libraries, we can easily update our library code and release a newer version without touching our final executable binary. Thus shared libraries are also very important in real-life production environments.

Looking forward

An important topic which is yet to be covered is the order of linking the libraries. Have a look at this article to understand the order of static linking.

That’s pretty much everything I had to say about linking in C++. For further reading and better understanding, go through the detailed working of the GNU linker.

Citation

@online{mark_gomes2019,

author = {Mark Gomes, Rohan and Das, Ayan},

title = {Static and {Dynamic} Linking},

date = {2019-01-05},

url = {https://ayandas.me/blogs/2019-01-03-linking-in-c++.html},

langid = {en}

}