Welcome folks ! This is an article I was planning to write for a long time. I finally managed to get it done while locked at home due to the global COVID-19 situation. So, its basically something fun, interesting, attractive and hopefully understandable to most readers. To be specific, my plan is to dive into the world of finding visually appealing patterns in different sections of mathematics. I am gonna introduce you to four distinct mathematical concepts by means of which we can generate artistic patterns that are very soothing to human eyes. Most of these use random number as the underlying principle of generation. These are not necessarily very useful in real life problem solving but widely loved by artists as a tool for content creation. They are sometimes referred to as Mathematical Art. I will deliberately keep the fine-grained details out of the way so that it is reachable to a larger audience. In case you want to reproduce the content in this post, here is the code. Warning: This post contains quite heavily sized images which may take some time to load in your browser; so be patient.

Random Walk & Brownian Motion

Let’s start with something simple. Consider a Random Variable

Realization (samples) of

Let us define another Random Variable

This is popularly known as the Random Walk. With the basics ready, let us have two such random walks namely

As of now it look all nice and mathy, right ! Here’s the fun part. Let me keep the time (i.e.,

It will create a cool random checkerboard-like pattern as time goes on. Looking at the tip (the ‘dot’), you might see it as a tiny particle. As it happened that this is a discretized verision of a continuous phenomenon observed in real microscopic particles in fluid, famously known as Brownian Motion.

Real Brownian Motion is continuous. Let’s work it out, but very briefly. We divide an arbitrary time interval

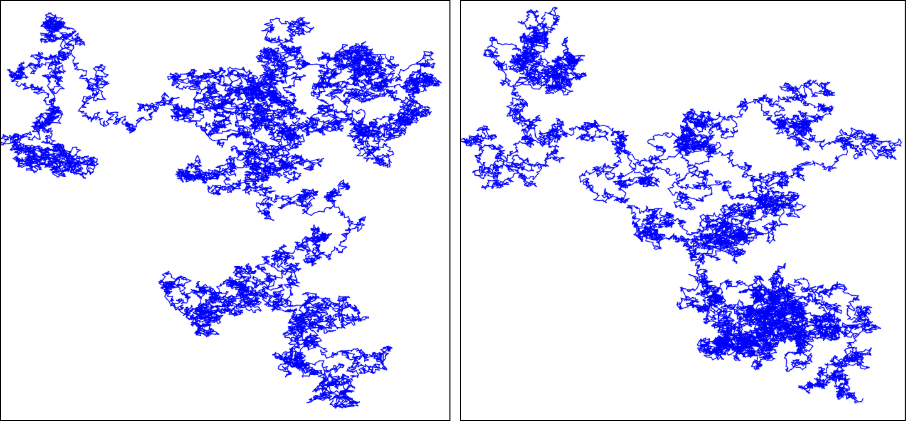

it gives us the continuous analogue of Brownian Motion. Similar to the discrete case, if we trace the path of

To make it more artistic, I took an even bigger

Want to learn more ?

Dynamical Systems & Chaos

Dynamical Systems are defined by a state space

The true states of the system at some point of time is determined by solving and Initial Value Problem (IVP) starting from an initial state

Having sufficiently small

Now this may seem quite trivial, at least to those who have studied Differential Equations. But, there are specific cases of

Lorentz System

Rössler System

Halvorsen System

Want to learn more ?

Complex Fourier Series

We all know about Fourier Series, right ! But I am sure not all of you have seen this artistic side of it. Well, this isn’t really related to fourier series, but fourier series helps in creating them.

We know the following to be the “synthesis equation” of complex fourier series

which represents the synthesis of a periodic function

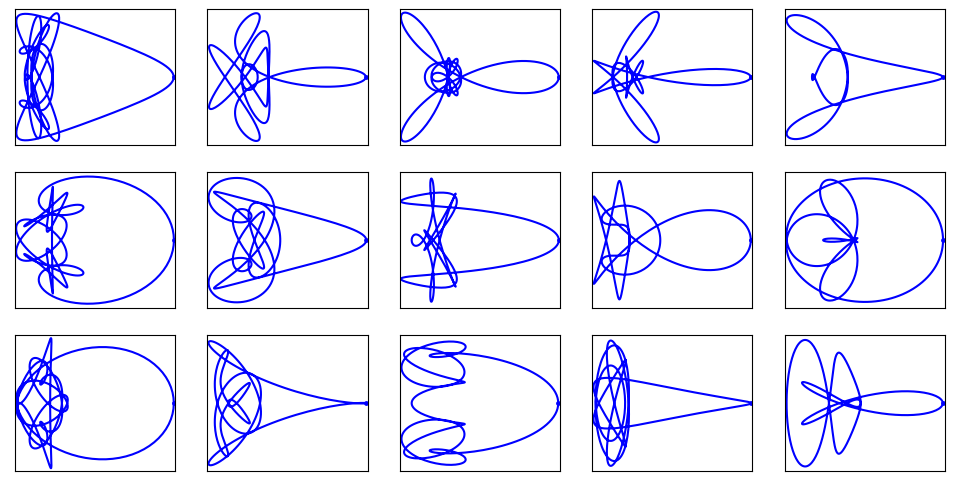

By doing this, we can make complex valued functions by putting different

We pick random

There is one way to customize these - the value of

Want to learn more ?

Mandelbrot & Julia set

These two sets are very important in the study of “Fractals” - objects with self-repeating patterns. Fractals are extremely popular concepts in certain branches of mathematics but they are mostly famous for having eye-catching visual appearance. If you ever come across an article about fractals, you are likely to see some of the most artistic patterns you’ve ever seen in the context of mathematics. Diving into the details of fractals and self-repeating patterns will open a vast world of “Mathematical Art”. Although, in this article, I can only show you a tiny bit of it - two sets namely “Mandelbrot” and “Julia” set. Let’s start with the all important function

where

Mandelbrot Set

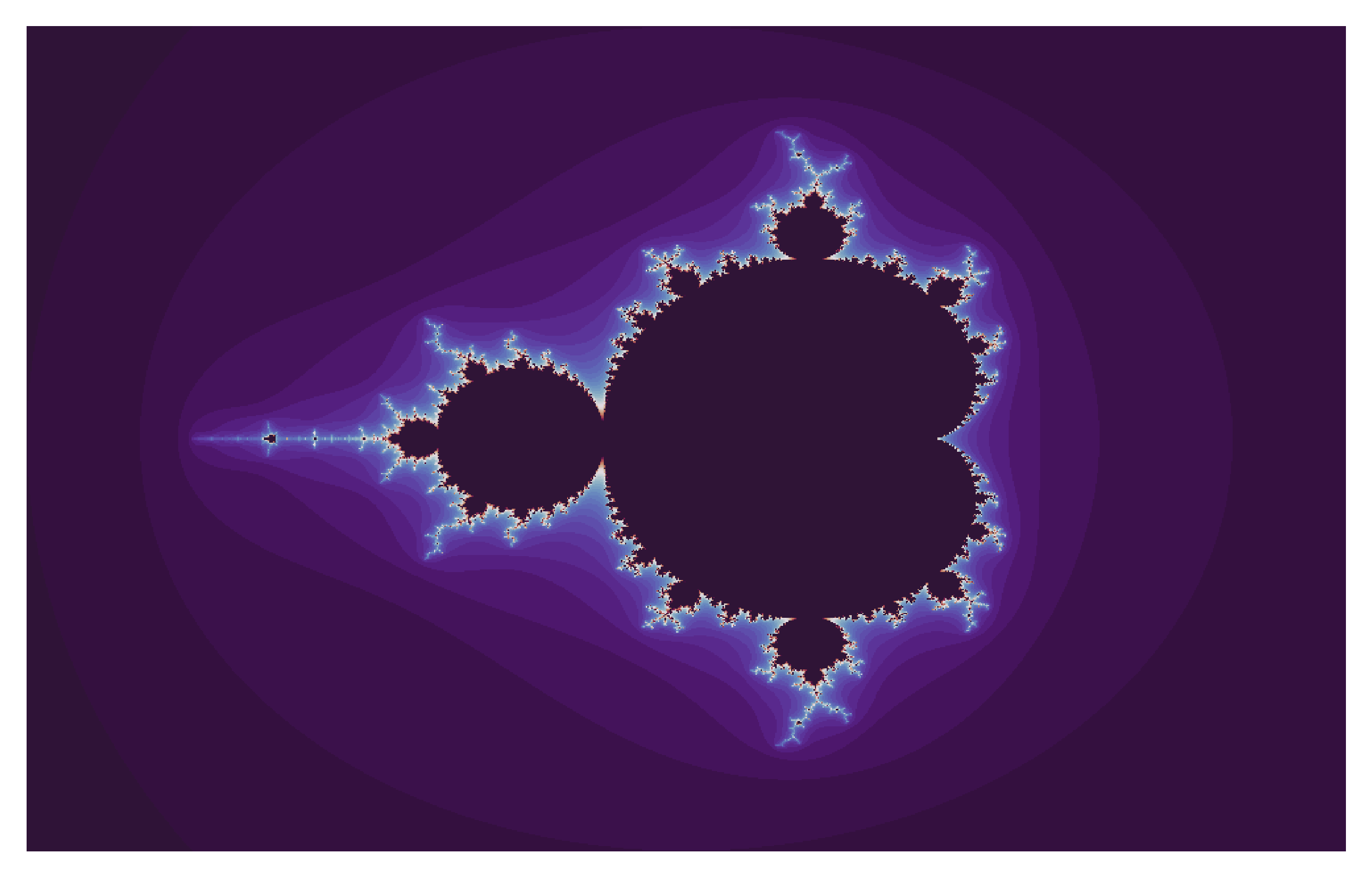

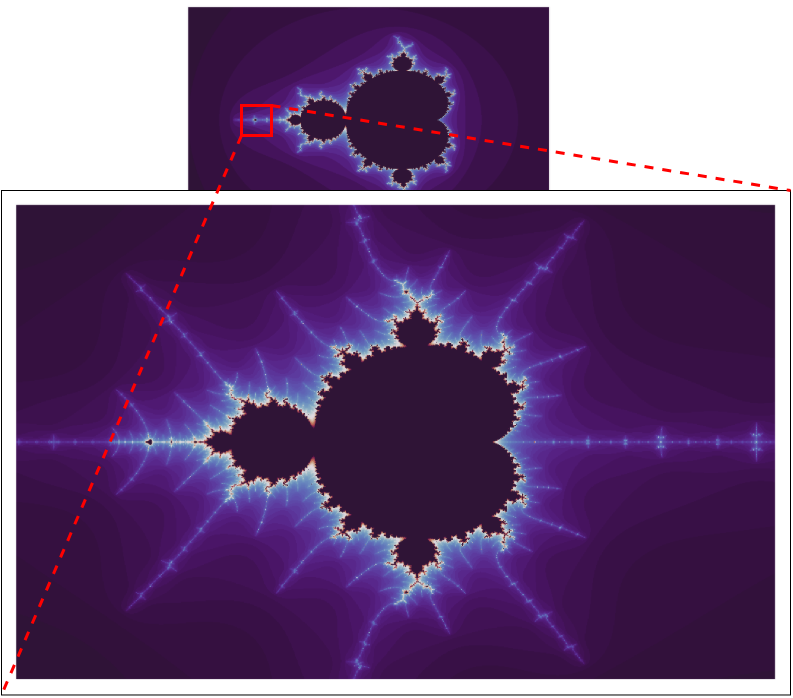

With these basic definitions in hand, the Mandelbrot set (invented by mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot) is the set of all

Simply put, there is a set of values for

It might look all strange but if you treat the integer plt.cm.twilight_shifted colormap for enhancing the visual appeal). The grid is in the range

What is so fascinating about this pattern is the fact that it is self-repeating. If you zoom into a small portion of the image, you would see the same pattern again.

Julia Set

Another very similar concept exists, called the “Julia Set” which exhibits similar visual

Please note that this time the set is parameterized by

Please note that as a result of this new definition, the

Want to know more ?

Alright then ! That is pretty much it. Due to constraint of time, space and scope its not possible to explain everything in detail in one article. There are plenty of resources available online (I have already provided some link) which might be useful in case you are interested. Feel free to explore the details of whatever new you learnt today. If you would like to reproduce the diagrams and images, please use the code here https://github.com/dasayan05/patterns-of-randomness (sorry, the code is a bit messy, you have to figure out).

Citation

@online{das2020,

author = {Das, Ayan},

title = {Patterns of {Randomness}},

date = {2020-04-15},

url = {https://ayandas.me/blogs/2020-04-15-patterns-of-randomness.html},

langid = {en}

}