Neural Ordinary Differential Equation (Neural ODE) is a very recent and first-of-its-kind idea that emerged in NeurIPS 2018. The authors, four researchers from University of Toronto, reformulated the parameterization of deep networks with differential equations, particularly first-order ODEs. The idea evolved from the fact that ResNet, a very popular deep network, possesses quite a bit of similarity with ODEs in their core structure. The paper also offered an efficient algorithm to train such ODE structures as a part of a larger computation graph. The architecture is flexible and memory efficient for learning. Being a bit non-trivial from a deep network standpoint, I decided to dedicate this article explaining it in detail, making it easier for everyone to understand. Understanding the whole algorithm requires fair bit of rigorous mathematics, specially ODEs and their algebric understanding, which I will try to cover at the beginning of the article. I also provided a (simplified) PyTorch implementation that is easy to follow.

Ordinary Differential Equations (ODE)

Definition

Let’s put Neural ODEs aside for a moment and take a refresher on ODE itself. Because of their unpopularity in the deep learning community, chances are that you haven’t looked at them since high school. We will focus our discussion on first-order linear ODEs which takes a generic form of

where

System of ODEs

Just like any other algorithms in Deep Learning, we can (and we have to) go beyond

With a vectorized notation of

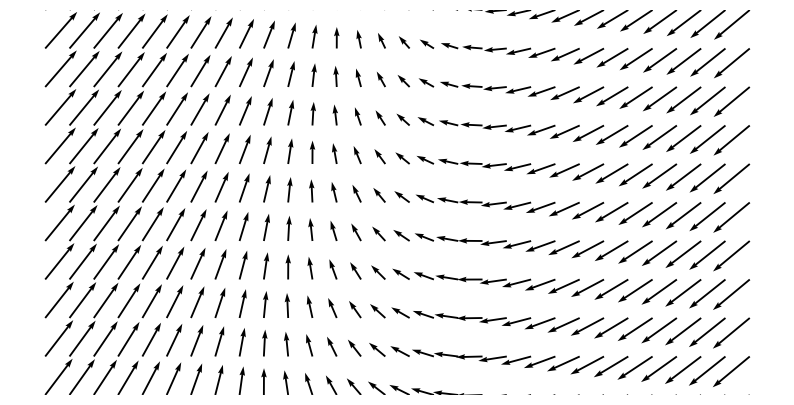

The dynamics

Initial Value Problem

Although I showed the solution of an extremely simple system with dynamics

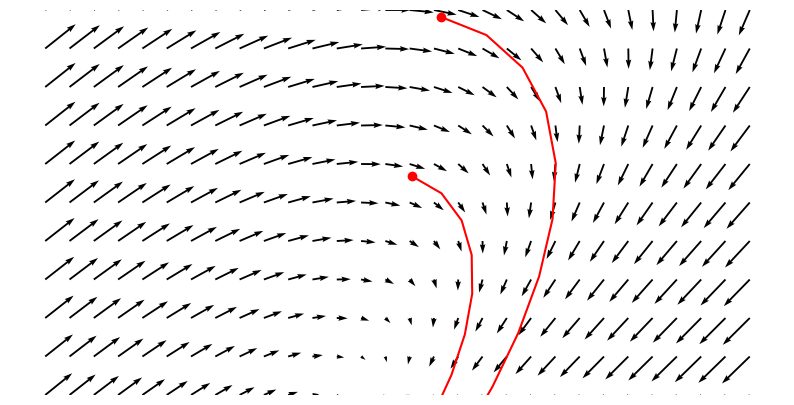

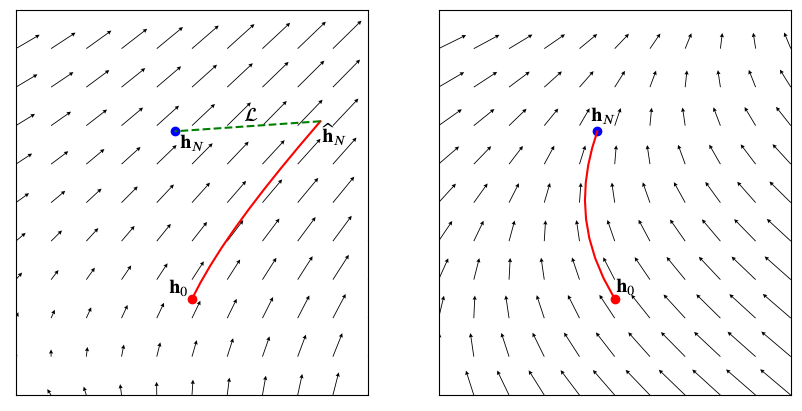

Fig.2 shows two different initial condition (red dots) leads to two different curves/solution (a small segment of the curve is shown). These curves/solutions are from the family of curves represented by the system whose dynamics is shown with black arrows. Different numerical methods are available on how well we do the “tracing” and how much error we tolerate. Strating from naive ones, we have modern numerical solvers to tackle the initial value problems. We will focus on one of the simplest yet popular method known as Forward Eular’s method for the sake of simplicity. The algorithm simply does the following: It starts from a given initial state

In case you haven’t noticed, the formula can be obtained trivially from the discretized version of analytic derivative

If you look at Fig.2 closely enough, you would see the red curves are made up of discrete segements which is a result of solving an initial value problem using Forward Eular’s method.

Motivation of Neural ODE

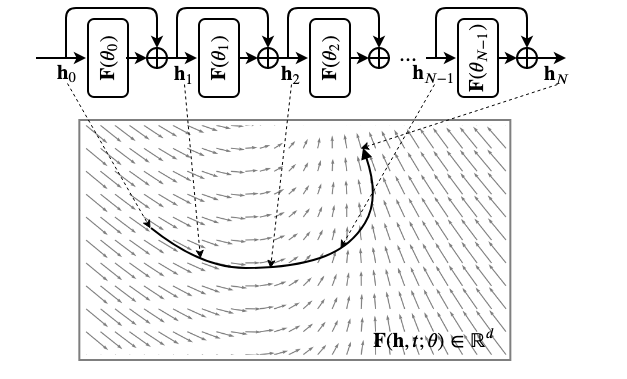

Let’s look at the core structure of ResNet, an extremely popular deep network that almost revolutionized deep network architecture. The most unique structural component of ResNet is its residual blocks that computes “increaments” on top of previous layer’s activation instead of activations directly. If the activation of layer

where

and

Parameterization and Forward pass

Although we already went over this in the last section, but let me put it more formally one more time. An “ODE Layer” is basically characterized by its dynamics function

where the “ODESolve” is any iterative ODE solver algorithm and not just Forward Eular. By the end of this article you’ll understand why the specific machinery of Eular’s method is not essential.

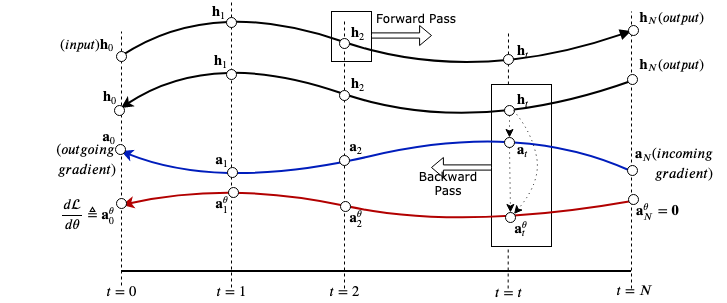

Coming to the backward pass, a naive solution you might be tempted to offer is to back-propagate thorugh the operations of the solver. I mean, look at the iterative update equation Eq.1 of an ODE Solver (for now just Forward Eular) - everything is indeed differentiable ! But then, it is no better than ResNet, not from a memory cost point of view. Note that backpropagating through a ResNet (and so with any standard deep network) requires storing the intermediate activations to be used later for the backward pass. Such operation is resposible for the memory complexity of backpropagation being linear in number of layers (i.e.,

“Adjoint method” and the backward pass

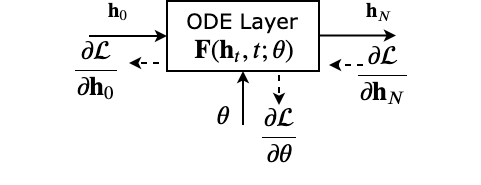

Just like any other computational graph associated with a deep network, we get a gradient signal coming from the loss. Let’s denote the incoming gradient at the end of the ODE layer as

In order to accomplish our goal of computing the parameter gradients, we define a quantity

comparing to a standard neural network, this is basically the gradient of the loss

and that’s a good news ! We now have the dynamics that

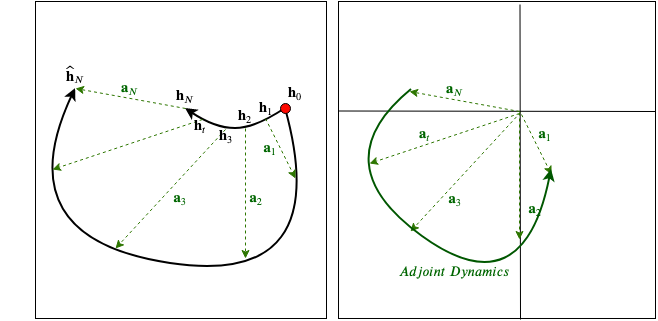

Please look at Eq.2 for the signature of the “ODESolve” function. This time we also produced all intermediate states of the solver as output. An intuitive visualization of the adjoint state and its dynamics is given in Fig.5 below.

The quantity on the right hand side of Eq.3 is a vector-jacobian product where

Its basically executing two update equations for two ODEs in one “for loop” traversing from

Okay, what about the parameters of the model (dynamics) ? How do we get to our ultimate goal,

Let’s define another quantity very similar to the adjoint state, i.e., the parameter gradient of the loss at every step of the ODE solver

Point to note here is that

just like shared-weight RNNs, we can compute the full parameter gradient as combination of local influences

The quantity

I hope you are seeing what I am seeing. This is equivalent to solving yet another ODE (backwards in time, again!) with dynamics

Take some time to digest the final 3-way ODE and make sure you get it. Because that is pretty much it. Once we get the parameter gradient, we can continue with normal stochastic gradient update rule (SGD or family). Additionally you may want to pass

PyTorch Implementation

Implementing this algorithm is a bit tricky due to its non-conventional approach for gradient computations. Specially if you are using library like PyTorch which adheres to a specific model of computation. I am providing a very simplified implementation of ODE Layer as a PyTorch nn.Module. Because this post has already become quite long and stuffed with maths and new concepts, I am leaving it here. I am putting the core part of the code (well commented) here just for reference but a complete application can be found on this GitHub repo of mine. My implementation is quite simplified as I have hard-coded “Forward Eular” method as the only choice of ODE solver. Feel free to contribute to my repo.

#############################################################

# Full code at https://github.com/dasayan05/neuralode-pytorch

#############################################################

import torch

class ODELayerFunc(torch.autograd.Function):

@staticmethod

def forward(context, z0, t_range_forward, dynamics, *theta):

delta_t = t_range_forward[1] - t_range_forward[0] # get the step size

zt = z0.clone()

for tf in t_range_forward: # Forward eular's method

f = dynamics(zt, tf)

zt = zt + delta_t * f # update

context.save_for_backward(zt, t_range_forward, delta_t, *theta)

context.dynamics = dynamics # 'save_for_backwards() won't take it, so..

return zt # final evaluation of 'zt', i.e., zT

@staticmethod

def backward(context, adj_end):

# Unpack the stuff saved in forward pass

zT, t_range_forward, delta_t, *theta = context.saved_tensors

dynamics = context.dynamics

t_range_backward = torch.flip(t_range_forward, [0,]) # Time runs backward

zt = zT.clone().requires_grad_()

adjoint = adj_end.clone()

dLdp = [torch.zeros_like(p) for p in theta] # Parameter grads (an accumulator)

for tb in t_range_backward:

with torch.set_grad_enabled(True):

# above 'set_grad_enabled()' is required for the graph to be created ...

f = dynamics(zt, tb)

# ... and be able to compute all vector-jacobian products

adjoint_dynamics, *dldp_ = torch.autograd.grad([-f], [zt, *theta], grad_outputs=[adjoint])

for i, p in enumerate(dldp_):

dLdp[i] = dLdp[i] - delta_t * p # update param grads

adjoint = adjoint - delta_t * adjoint_dynamics # update the adjoint

zt.data = zt.data - delta_t * f.data # Forward eular's (backward in time)

return (adjoint, None, None, *dLdp)

class ODELayer(torch.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, dynamics, t_start = 0., t_end = 1., granularity = 25):

super().__init__()

self.dynamics = dynamics

self.t_start, self.t_end, self.granularity = t_start, t_end, granularity

self.t_range = torch.linspace(self.t_start, self.t_end, self.granularity)

def forward(self, input):

return ODELayerFunc.apply(input, self.t_range, self.dynamics, *self.dynamics.parameters())That’s all for today. See you.

Citation

@online{das2020,

author = {Das, Ayan},

title = {Neural {Ordinary} {Differential} {Equation} {(Neural} {ODE)}},

date = {2020-03-20},

url = {https://ayandas.me/blogs/2020-03-20-neural-ode.html},

langid = {en}

}